We had a chance to sit down and talk to Maurice about his new book, his research approach and what he would do if he was mayor.

Blake: All right, so we've known each other for many many years. I knew you in your first permutation as a lawyer.

Maurice: That is right.

Blake: A lawyer in New Orleans. The Napoleonic code. Why would you possibly want to give up on that profession and become a hardworking writer?

Maurice: I mean, it was so much fun, you know, all those documents and like all those weird anachronistic terms, you know, but I had to give it up man. There was something greater was out there for me. This is where I am now.

Blake: What's the writing bug that you have? Was it something you always had or was it slowly brewing over time? Were you starting off with blog posts and articles or did you immediately dive straight into being a novelist?

Maurice: I definitely always had it.

I think that most writers are those weird kids who, you know, they kind of sit and observe everybody else. People are like, why are they so quiet? It's because that person is just looking and is taking their time to take it all in. And at some point, if they're lucky, it comes out either in writing or some other creative endeavor.

So as a kid, I was that kind of a kid. But I think that it took me a long time to figure out what it actually meant. I could write books, write shorts, write essays and that sort of thing.

Blake: So the confidence level grows, grows over time and then you kind of made the jump. What about like five, six years ago?

Maurice: Yeah. 2019 I cut the cord finally. I figured if the streaming service could get us off of cable, I could cut the law thing and go straight into writing.

Blake: Nice. How many books has it been so far? Three now?

Maurice: This is my third book in five years the newest book.

Blake: I'm at around Chapter 11 currently. I won't say exactly what just happened in the book, It's a big moment in the in the story. But I was curious about where the story stemmed from? Was there some specific links in your family or your own roots in New Orleans? What are your roots to the city specifically? And did you tap into that for this story of of slaves and antebellum South?

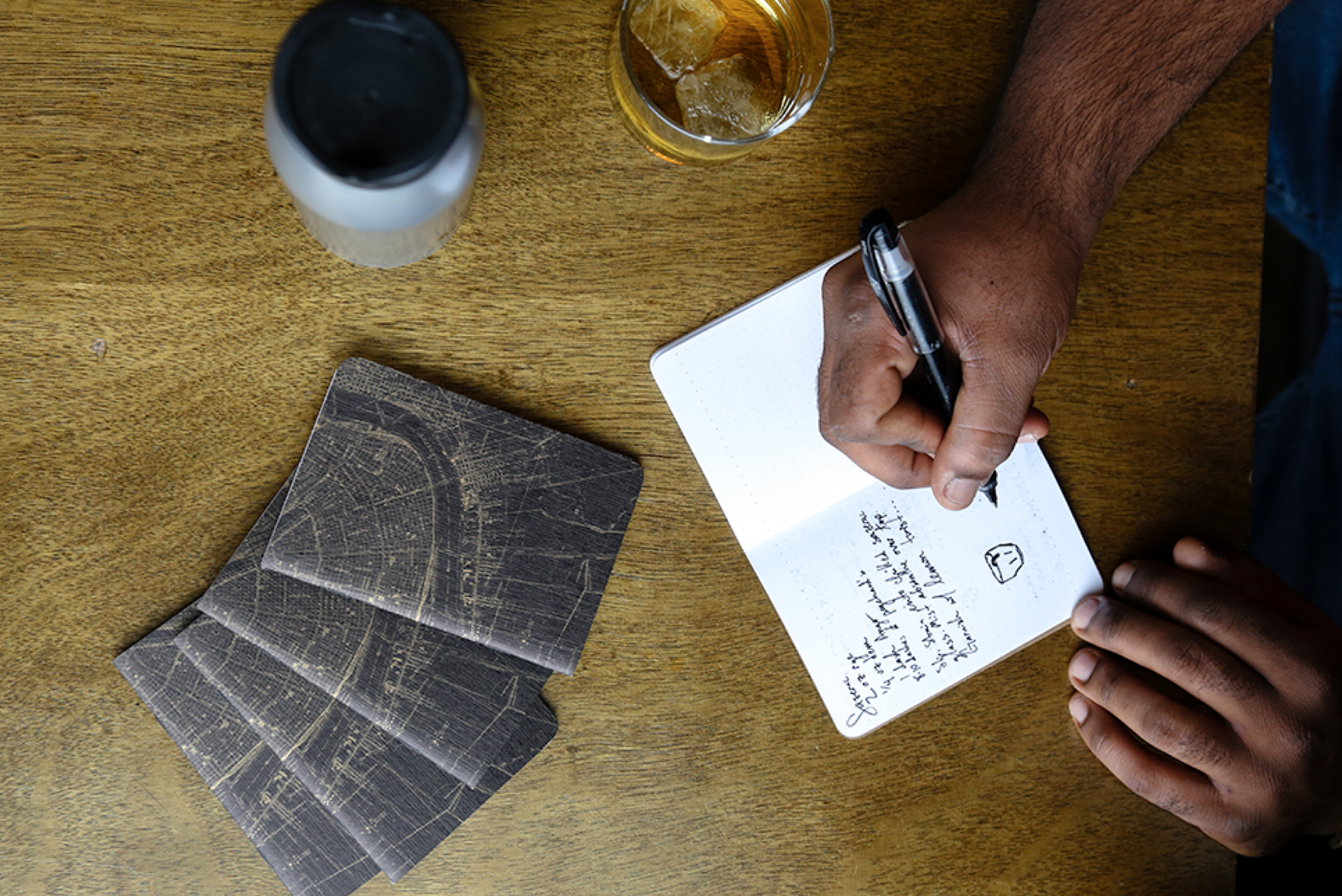

Maurice: Oh yeah, absolutely. Well, you know, everything is connected. So, for example, I would get bored in my office and I'd go down to the French Quarter where there is these archives.

There's the Historic New Orleans Collection, for example. And I would find these these manuscripts and old documents that were explaining what happened in the past. And I found the document that talked about how the Confederates refused to fight in New Orleans when the Union showed up. Now everywhere else in the South they fought, you know, fought their butts off.

Virginia, Georgia, yada, yada, yada. But New Orleans, they broke their own guns and they burned their own uniforms and they sunk their own ship. They had one ship in Lake Pontchartrain. They sunk their own ship. And the documents don't explain why they did that. This is literally 20 years ago that I found this document. So I thought for this for the past 20 years. Why was that the case?

And one day I think I was talking to my mom about something, and I thought, okay, now I think I know what happened. And it's speculation, but if my mother, grandmother, wife, and cousins, and aunties existed in that time period, they were probably trying to sabotage the Confederates, you know, poisoning those guys and, you know, putting glass in their soup and, you know, making their horses get angry so they get bucked off and they break their necks, that kind of stuff.

And there are a lot of those kind of reports that happen in real life. And my family has activists in them. My grandmother was an activist. My mother has been somebody involved in community work. So I figured, okay, if you put those two ideas together. It explains the gap. It explains why those guys couldn't fight because they were probably terrified.

You know, they had an enemy coming from outside and within at the same time. So just give up and fight another day.

Blake: So there are specific, specific relatives you had that you sort of use as your inspiration to then create this work of fiction that obviously has plenty of historic, truths to it that you're pulling from. What other research did you do to kind of put the book together?

Maurice: Well, you know, sometimes research for an artist is other fictional universes. So, you know, even reading Toni Morrison or watching like Twelve Years a Slave or watch an anime. There's all these sort of stories about people trying to get the liberation.

It all comes together. But I think what really set me off was when I was at Grisham House in 2020 during a pandemic. And I went on Facebook and asked some friends, just send me whatever research you have any books you have about New Orleans history. One of my buddies, Veronica, up in Massachusetts, sent me a box of 17 books.

I couldn't read all 17, but I went to like, each book read 50 pages, and I kept finding these sort of seeds for a story. There was a woman who was so wealthy in say 1820 or so, that she decided to build a school for black kids, because there were no public schools back then. It was against the law to have public schools for black kids.

So she uses her money to make a make a school. I kept thinking how she has so much money. Well, because half of the people in the city who were black were enslaved, but the other half were free. And they had iron making companies and they had ship building companies. They had their own property and their own savings. The community was full of people like that, who were doing work to make it a better city for people of color.

Blake: I noticed in the book, there was some, a specific phrase in the very beginning that you continued to repeat, and I appreciate you repeating it. And I felt like it was sort of setting, if there is a message in the book, the phrase was "Slave labor camp, also known as a plantation."

At least seven times in the very beginning, you use that phrase over and over again to kind of really nail down why you were writing this book. At least that's how I was reading it as your audience. So can you talk a little bit more about that?

Maurice: Well, you know, the idea. It was really simple.

If you say plantation, people have different ideas of what that is. It could be a place you're going to have a wedding. You know, it could be a very nice place to go to a cabin and have a little vacation with your loved one. But if you say slave labor camp, also called a plantation, you kind of go, oh, that's what was happening here back in the days.

Because whether or not, you know, the place had, you know, five enslaved people or a hundred, they were not there of their own free accord. They couldn't walk away. And so I think in the book I was trying to remind people of what it may have been like. And that's the repetition I get from Toni Morrison. She has a book called Song of Solomon. She has certain phrases she uses over and over again. And it seems sort of clunky. But because she was such a master, you know, she's doing it on purpose. And so I'm doing the exact same thing. To me it's a speed bump. So you cannot forget what we're talking about when we say plantation in the book.

Blake: So far, what has been the response to the book? I mean, I know it's only been out for about a week or so, but have you heard from anyone who might be a historian or who has lots of in depth knowledge around Antebellum South, New Orleans, and sort of what their feedback is on the book?

Maurice: Oh, yeah. You know, they wouldn't dare say anything bad about it. No, I'm just kidding. But, so this is my third book. It's the biggest response I've had so far. Um, reviews from the New York Times, the LA Times, the Atlanta Journal Constitution. I found out like three hours ago that it's now in its third printing.

That means that it's selling so fast that they can't keep it on the shelves in the independent bookstores. I can see reviews from lay people online, you know, Goodreads and Amazon. And people seem to like it. You know, I think that, some may question certain choices, but as an artist, you're always trying to make things not too simple.

You want things to sort of have a little, a little tug to it. They should read it and experience it and feel a little unsettled by it. And, and so the response has been great. And also when I was writing the book, I talked to a lot of, historians. I mean, Fatima Shaik is a local New Orleans journalist and writer who knows more about history than I ever will in my entire life. I relied on her. I talked to a friend named Dan via Twitter. He lives in the city. I asked "Hey, Dan, how do you buy a pair of glasses in 1857?" He's like, "you go to a jewelry store", that kind of thing. So You know, I covered my back the entire time.

Blake: That's interesting.

Yeah. Asking, so you don't find yourself, you know, I guess when you're writing, you do find yourself in a possible roadblock of being like, what would my character do in this moment? Like buying the glasses or certain decisions of, you know, vehicles, transportation, cartography, how are you making it from A to B a hundred some odd years ago.

Maurice: There's always something I have in the book, when they're traveling around the French Quarter, something called an Omnibus. And so I put that in there, and at first I think, it was an early reader who was like, what is an omnibus? And some reader put online, is it like a futuristic flying bus? But it was an actual thing.

It's just basically like a sort of a shuttle that was drawn by horses back in the old days, and it was called an omnibus, which is an old fashioned word for, a public bus.

Blake: You mentioned the author, Shaik?

Maurice: Yeah, Fatima Shaik.

Blake: She the one who wrote the book about Economy Hall last year?

Maurice: Absolutely, absolutely.

Blake: Yeah, I heard a little bit about her, I believe the story, I may be wrong, but that her father was walking down the street and they were throwing out all these documents. They were actually the written history of not just Economy Hall, but essentially the written history of Treme. Thankfully he was able to acquire them and then they sat on a shelf. Then I guess at some point she inquired about them.

You know a little bit more about that, like how she wrote that book or where that story came from?

Maurice: You told us the story right. That's exactly what happened. And her father was a hero for doing that. She's a hero for doing what she's done. And, you know, in that book, what she's doing is she's trying to show people that the people who were operating at that time were really brilliant people.

They were doing their best to exercise their freedom as Americans. And, It's a beautiful book and people like her have inspired me so much her, Tony Morrison, Jesmyn Ward, many other writers who have written these historical works, I rely on them to get to where I go in my writing.

Blake: Have you ever thought about like while writing it, the possibility of building out an expanded, almost like a glossary or expanded a little addendums that you could create. I mean, at least that's where my brain goes in terms of like creating more content around the content itself.

Maurice: I would, I would totally do that. There's actually, a colleague of mine at LSU, he just did. 2,500 pages. I think it's for Dungeons and Dragons and it's a published book that he's doing. He just put out.

It's all part of the Maurice Carlos Ruffin cinematic universe. You know, all my books, all the characters, all the settings, it's just one big multiverse. And so to me, it's all connected. So I would totally do that. As a guy who grew up reading X Men and Captain America and Fantastic Four, I would totally do that.

Blake: I'm guessing you are, based off what you just said, the type of person who love books where, a third or a fourth of the pages are the footnotes.

Maurice: Oh, yeah. Oh yeah.

Blake: Where you just go these deeper and deeper dives into the idiosyncrasies of a certain person. Phase of Time. You know, what inspired that sentence or paragraph. I'm a huge fan of the rabbit hole.

Maurice: Oh, absolutely. Not just online, but in print.

I mean, the Watchman, for example, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. That graphic novel has so many little, has sop many little rabbit holes and warrens in it. And then also writers like Nabokov, he was the kind of guy who would just throw out like a French phrase and you're like, why is he putting a French phrase in his book. You look it up and you go to the footnote and you see that he's like referring to some English story from 400 years before that was based on a ancient Roman story that's based on an ancient Egyptian story.

And to me, that's satisfaction, to have these connections between the present stories and the past stories. And that's why in my book, The American Daughters there are these sort of inserts, these documents that I put into the text, there's a map, for example. There is a slave bill of sale that's also in there and other documents as well.

It makes it feel more filled out.

Blake: Right. The history of New Orleans, how much of that did you know before writing the book? How much of your own studying of New Orleans went into inspiring the story that you just wrote?

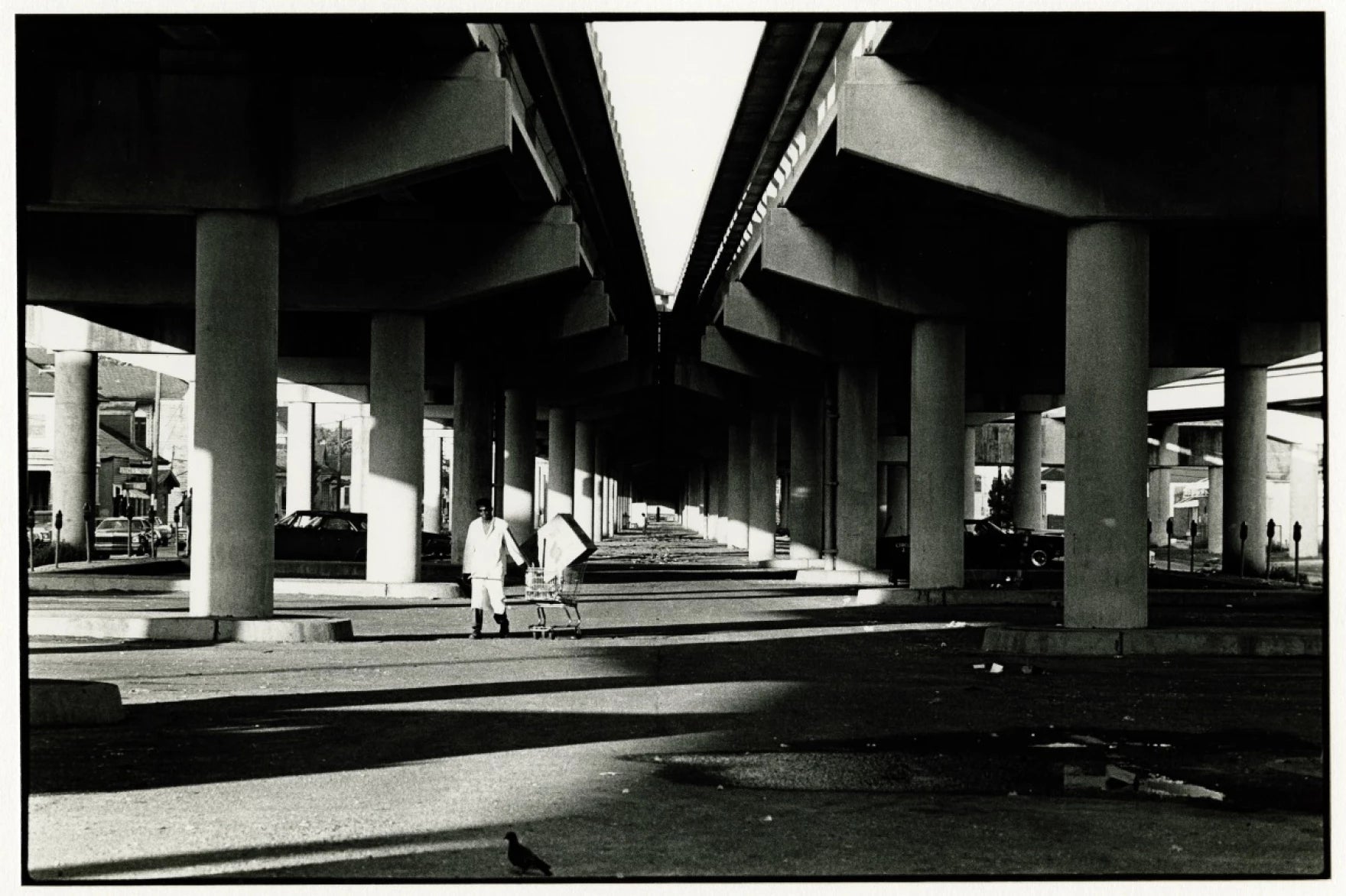

Maurice: Yeah. Great question. You know, the thing about it is that every place has a history and New Orleans is special because it has so much history. If you go to 1850, for example, this was one of the most diverse cities, maybe in the world at that time. I think we were second only to New York in terms of population.

And we were one of the wealthiest cities in America as well. And so if you come here back then you're going to see people walking around the French Quarter who are from France, China, Turkey, Africa, you know, these are different places. You know, on top of the sort of Scottish, Irish, German, you know, those kind of people in the city.

And I think that when I was coming up, I was aware of some of these things. I had mentors when I was in high school who would say, you know, this is our history. But when you're young, you just kind of say, "ah, whatever." And I think one of the pleasures of being a New Orleanian is that the more you, the more you sort of dig into it, the more you're going to find.

Because the history is so complex, it's never ending. It's just never ending. You can always find new information, always find new rabbit holes to go down. And Just talk to a native New Orleanian. Ask them their family's history. It's always more complicated than you think. One example was, there's a family called the LeBranch family.

If I say, what is their ancestry? You might go, LeBranch? They're probably French. Well, it turns out they're actually German. And when that family came over in like the 1800s or whatever, somebody, pointed at a tree and he said, LeBranch in German. And the person says, Oh, you mean LeBronch? And so they think that that's the family's name, and they become the LeBronch family from now on.

So there's all these just hidden things in the city that you can play with as an artist, and our musicians do it constantly. You know, our painters do it, our actors do it. I do it as a writer, and it's just so much fun, and I have a lot more work to do in that respect.

Blake: I found when I was reading the book, um, it was kind of, you could tell that there were all these different, Uh, personalities, accents with any story, but I then wanted to go listen to how you.

Uh, tackled the audio books. I'm always kind of fascinated by some of the books, they just sort of read it straight, but other ones are more, it's like a teleplay. It's like, like old radio. And I definitely, I listened to about five minutes of, of who, who did the narration for the book?

Maurice: Lynette Freeman.

Blake: She did an amazing job. Nailing male, female characters, young, old, accents and stuff like that. How involved are you personally? With working with someone like her to kind of try and direct the tone of the characters themselves when she's doing the recording.

Maurice: Just a little bit, you know, it's really like a casting call.

They send me audition tapes of the different actors who are going to perform. And just like a real, like a movie for example, I think you look for the essence of that person. And so in comparing the actors, um, I found that she just had the right. Um, the right tone and she had a great range, you know, she could do different voices, different accents and in the audio book.

She just really nails it time and time again. It's really incredible.

Blake: Yeah, it was, I was really impressed. It's definitely something once I finished reading, I want to go through and sort of listen to her, um, her recording, uh, of some of the specifically some of the chapters that had, or I guess a bit more action packed, if you will.

The audio book itself, and you mentioned earlier, sort of your cinematic universe. I definitely found or have found so far with reading the book that this is, you know, not very far away from taking a leap into a, you know, a screenplay. Have you thought about trying to take something like this and, well, maybe shop it out to turn into a screenplay to turn into a film. Shop it out to someone like Netflix?

Have you ever considered tackling the screenplay yourself?

Maurice: Well my books have all been optioned by people in Hollywood. It's in various states of production or non production. Um, initially I always said I would not want to do my own screenplays. I didn't want to be distracted from the work of writing my novels, but I've changed my mind in the past couple years.

And so if I have an opportunity to do that, I'll write my own screenplay. I've done some sort of samples and sort of test cases and I really enjoy writing screenplays. It's a different, um, medium. And you can play with the stories in ways that are, to me, very fresh. I really enjoy doing that.

Blake: I've picked up a few screenplay books over the years, like especially when I'm in like New York, I go to the Strand bookstore, they've got a whole screenplay section in some back basement corner.

Maurice: Oh Yeah.

Blake: I picked one I picked up was Inglorious Bastards by Quentin Tarantino. and Reading how he describes a scene and works in humor. It's fascinating. But what's really interesting is reading the screenplay and finding the scenes that are not in the movie. Almost like watch the editing process. How they're cutting certain things out or hearing a backstory on a character. You know, being someone who loves film and novels is, you know, endlessly fascinating.

Maurice: Tarantino is so great. I mean, his work is fascinating. And of course, he directs his own work. So to see him make those changes are really interesting to me.

I love to watch films and to think about how stories, um, can be adapted. I mean, this was a good year for adaptation. We're not getting too far off track. I mean, Barbie, Oppenheimer, uh, American fiction, all these big movies came from previous sources and I know many of the earlier sources. So it's fun to sort of think about the differences between the one and the other.

Blake: Yeah. What is your of hometown right now? Are you in New Orleans? Is New Orleans home? Or are you sort of bouncing around?

Maurice: New Orleans is home. I teach at LSU. So I have a place near the University. So it's easy to get to my students when I have to. New Orleans is home.

You know, it always will be. And it's been interesting because I'm on tour right now. So I'm getting these different flavors as I move around from place to place, you know, Memphis, Houston, I'm going to DC and that kind of thing. There is no place like home. New Orleans is so special and so different from everywhere else.

Blake: What's your take on the current state of the city right now. I have my own personal opinions growing up here. Coming back. I see the five years before Katrina, the five years after, the five years after the Super Bowl win on into Covid. Each one kind of has its own good parts and bad parts. What's your take on it?

Maurice: Yeah, I recall we talked about this on a video maybe 12 to 13 years ago. And that was a situation where it was post Katrina and people were coming in from out of town. And I was very bullish on that idea, just come down here and be a part of the economy and that sort of thing.

But now I think I have more wisdom, and the way I see this city, knowing how our history has played out, is that New Orleans is always kind of a mess, but in a good way. It's a city that is in perpetual transformation all the time, constantly. And there's an energy to it. You know, this city's not for everybody.

You know, if you want to be totally organized and put together, you're not going to enjoy it. It's not New York or Chicago or L. A. or San Fran or something like that. But if you want the sort of essence that comes from this, this gumbo, you know, this idea that we have this great African heritage that came to us through Haiti, for example.

Now we have this great, Latino heritage, people that came in after Katrina. We have the French heritage. We have the Native American heritage. It gives this city a flavor that's so unique. You know, you walk around, the architecture is not like anywhere else in the country. The language is different, the people are really nice.

I mean, even going around the South, which is a pretty nice place, we're amongst the nicest people around. So, I worry sometimes. But frankly, we've always worried about this city. And our response to that is to have a good time. To be good to each other, to be in community. You know, to share a bowl of red beans and rice and go to the parades together.

And I think that's who we always going to be until the last drop of water comes in and wipes it all out. We'll still be partying and smiling at each other and playing music.

Blake: Yeah, I wrote something, when the sweet 16 of Katrina came along and literally the day of the storm coming through and shutting the city down for three weeks.

It's an old idea. It's basically just that New Orleans is New Orleans because of the people. And as long as these people choose to be here, no matter what. As long as those people are here to choose this place, choose to live here... the sort of modern Pompeii, if you will, on the precipice of destruction all the time, it'll always be what it is.

And I see that on, online, when I look at like the New Orleans Reddit, there's always people, you know, who complain about the city and like, "ah, I'm moving or I, I'm so glad I moved and I live in wherever." But so often there are people who are like, Guys, I moved to Southern California. It's beautiful here. I hate it. Because they're just like, you know, I don't know anybody you can know and no one's not that everyone mean, but like, you know, you don't have the same, "Hey baby", you know, you get conversations with your neighbors or strangers or there are no strangers, you know, and I think elsewhere, that's just not the case.

And it does feel like a little bit of an alien existence when you're outside the city, not to, you know, we can blow new Orleans up all the time and try and say it's the greatest thing ever. It's not, but it is this incredibly special thing that once you have that. Special relationship with it. You really, it's really hard to shake.

Maurice: Yeah, it's America's biggest small town. That's the way I think of it. You know, we seem like we Have figured out a pretty good balance between having the benefits of culture. You know, we have so much music and we have so many plays and we have movies and that sort of thing, which you don't get in a lot of small rural towns.

But at the same time, most of us know each other. You're not just coming over here. I was having lunch at a salad bar and I thought I was by myself and There was a lady looking at me from across the room. She was like, Hey, Mr. Ruffin. And I'm like, Oh, this is a judge. I used to know back in the day. I hadn't seen her probably in 15 years.

And she was like, how's the family? How's your mama doing? That kind of thing. And that's new Orleans. You're never by yourself here. And that's a wonderful experience to have.

Blake: What's your, what are your thoughts on, or hopes if you will, for the city in the next, you know, 5, 10, 15 years, you know, what are you kind of hoping to see To happened within within the city. I mean, obviously there's things that can be done to change the problems that we have. But, you know, I guess the one of the quickest ways to ask this is like, Maurice decides to hang up being the writer. You had a good run, you produced some movies, and now you're mayor.

What does Maurice Ruffins, the mayor of New Orleans, do?

Maurice: Don't wish that on me, please.

Blake: Okay, what do you do? What are the first hundred days? What are some of the things that you would hope to put into play?

Maurice: Well, I mean, the thing about this city is that we have the sword of Damocles hanging over us because of the environmental issues.

So, you know, the wrong storm at the wrong time could really just change things for a long time. My belief is that with climate change, We will experience some pretty bad flooding. Who knows when it's going to be? Will it be a hundred years from now, five years from now? Who knows? But even thinking about that, as you said, people will still be here, you know, kind of like Venice was after it got flooded the first time, people will always want to be here.

For me, this city, I think what it really needs is some reform and education. I think that, I think that amongst different demographics in the city, you know, racial demographics and, immigrant status, there's a real divide between the haves and have nots. And so I think that when we look at our public schools, they're underfunded, under resourced.

I think that a lot of the kids are brilliant, and they often feel a little sad because they can see that there's things they can't quite reach based on lack of opportunities. And as somebody who's worked with, you know, fellow lawyers who would send their kids to some of the fancier schools and spend $40,000 per year to send these kids to these schools, I would argue to all of us, it makes more sense for us to come together as a community and find some way to equalize these schools, because if you're paying $40,000 to send your kid to school, that's a tax, basically, you know?

And At the same time, if you're sending your kids to other schools and they're just having like a bad situation where they're not getting educated or whatever it is, we can fix that. So as mayor, I would try and make that one of my main things. I think if you give the kids hope, that's what the future really is. You probably have less crime, you have, less sadness, less loneliness and less incarceration. And so I'd focus on those things as mayor. And I think the upshot of that would be a city that is rejuvenated and more together.

Blake: All right, I'm in. I agree with all of that. I think my hope would be whoever does wind up being mayor next. That they would try and establish a brand narrative. Try and get everybody on the same page, like, this is where we're going. You know, we had that after Katrina, we were forced to have that. And then, I think there's a need for corralling the troops, getting everybody on the same page.

Trying to find a way to produce a little bit more of that solidarity that I think we had right after the storm. And we still have it. People want the city, we're choosing to live here, they want it to go in a better direction. But I think it's important to speak up for everyone and get everybody on the same page.

Maurice: I agree.

It takes leadership. Somebody has to stand in front of the entire city and say, this is the way forward. And I think because of how we're built, we have the greatest opportunity to come together in ways that we've never seen anywhere else in the country. And you know, maybe to want paradise is too much, but we were so close to it in New Orleans with our life standards.

You know, the idea that this is a place where people, this slower pace is good. The idea of spending time with your loved ones is good. And we can figure out the last pieces that I mentioned earlier. That's going to make us as good as it gets for an American city.

Yeah. Yeah.

Blake: Yeah. Well, thanks, dude. I think this has been great.

Maurice: Thank you so much, Blake. I really enjoyed this.

Blake: Yeah, I, uh, I'm very glad that your books are gonna be blockbuster movies soon.

Maurice: It's only a matter of time. I'll give you a cameo.

Blake: Alright, dude. I appreciate it. Thank you.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.