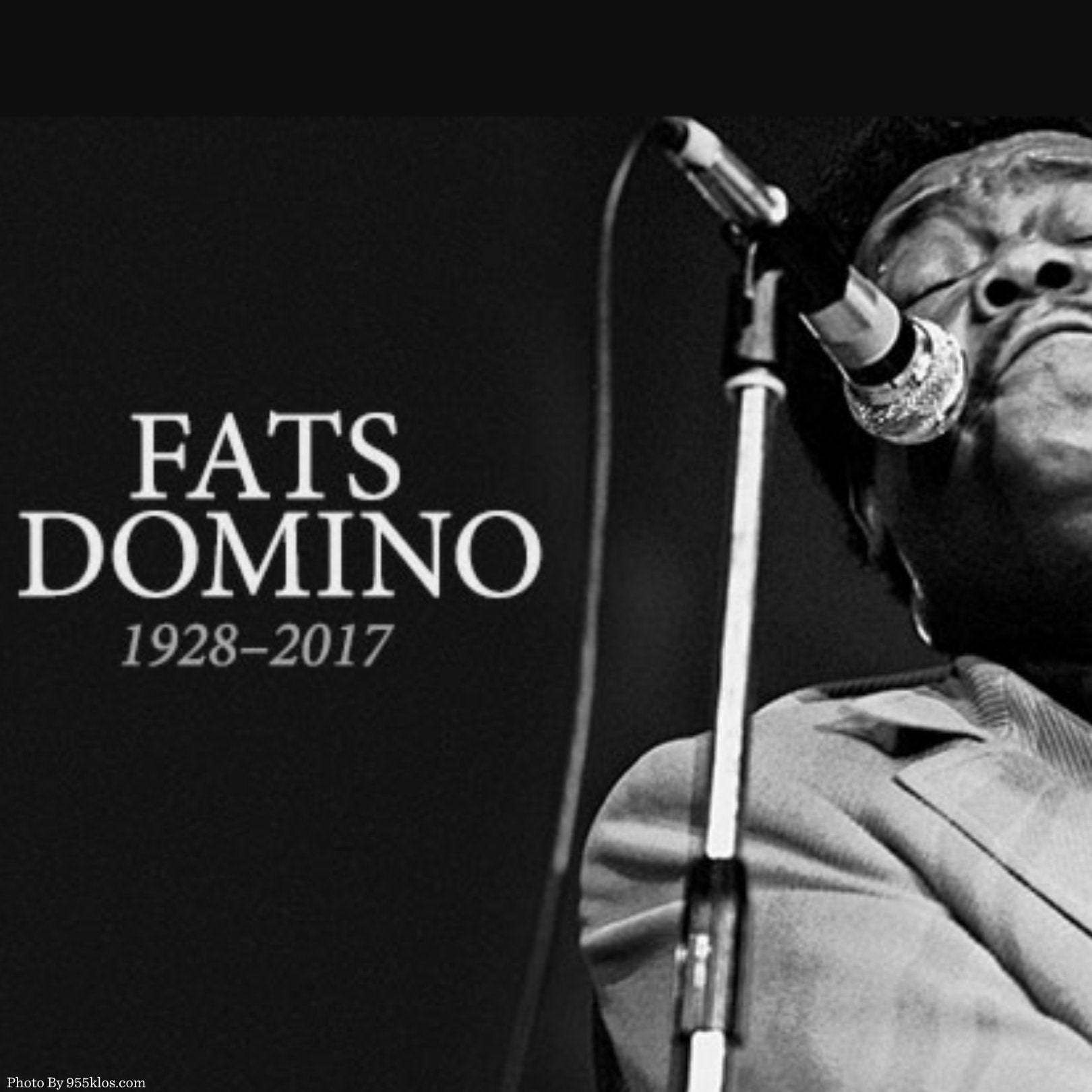

“What they call and rock and roll now’s rhythm and blues I’ve been playing for fifteen years in New Orleans.” –Fats Domino

Beloved by his home city, idolized by musicians as varied as Little Richard, Randy Newman, and the Beatles, and selected as an inaugural inductee in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Fats Domino was one of the best-liked and most influential figures in 20th-century popular music. His longtime partnership with bandleader Dave Bartholomew would yield dozens of hits, including “Blueberry Hill,” “Ain’t That a Shame,” and “Walking to New Orleans.”

Born in 1928 in a shotgun on Jourdan Avenue in the Lower Ninth Ward to a Creole family hailing from Vacherie, Louisiana, Antoine Dominique Domino Jr. was fascinated with music from a young age. At the age of eight, he started learning piano from his brother-in-law, jazz guitarist Harrison Verrett, who wrote the notes on the keys for the precocious pianist. Domino would leave school in the fourth grade, collecting scrap metal to support his family and continuing to hone his musical gift in his parents’ garage.

Domino was mostly self-taught, listening to records over and over on jukeboxes (black music largely hadn’t yet reached the radio) until he could play them himself. His style, influenced by the boogie-woogie of Pete Johnson and Amos Milburn, incorporated piano triplets, a musical trope that would become central to early rock and roll. Bandleader Billy Diamond gave Domino the nickname ‘Fats’ after the jazz pianists Fats Waller and Fats Pichon. Domino’s stature—he came in at 5 ‘5 and well-over 200 pounds—ensured that the name stuck.

At fourteen, Domino started playing gigs at juke joints around New Orleans, including the Hideaway Club, where he was discovered by Lew Chudd and signed to Imperial Records. Domino’s first record, a spirited and exuberant 1949 reworking of the standard “Junkers’ Blues” called “The Fat Man” would become a hit, selling more than a million copies by 1951.

It was the start of a long string of hits for Imperial, most recorded at Cosimo Matassa’s studio, J&M Recording, tucked in the back of an appliance and record store on North Rampart street. In 1956, Domino hit the big time, scoring multiple hits (including his version of “Blueberry Hill,” “My Blue Heaven,” and “Blue Monday.” That same year, Domino appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, and logged cameos in the films Shake, Rattle & Rock and The Girl Can’t Help It.

Mainstream success demanded that Domino and his band tour extensively—a chore made more complicated by segregated hotels and restaurants. In 1957, Domino would log more than 30,000 miles and play 355 shows—a schedule that inspired intense homesickness for the band members.

A naturally humble, shy, and affable family man, Domino was an unlikely father figure for rock and roll, a genre characterized by rebellious snarling and vainglorious showboating. While Domino had a penchant for showy jewelry and flagrant spending, his persona was never threatening. This very acceptability—his portly stature was sometimes used to neuter him in an era plagued by the racial-sexual panic of insecure whites—allowed Domino to serve as an unsung figure in integrating young audiences. His crowds were some of the first to contain both white and black teenagers—a dangerous proposition when alcohol was also at hand. When riots did break out at his shows, Domino was careful to explain that rock and roll weren’t to blame.

1963 saw the end of Imperial Records and the beginning of Domino’s slide from a cultural dynamo to legacy act. A contract with ABC-Paramount (and without Bartholomew) wouldn’t yield the same commercial or artistic results as his New Orleans days.

Domino would go on to travel the world for the next three decades until a bout of sickness while playing in Europe in 1995 brought his touring days to an end. A famous homebody, Domino played only in New Orleans afterward, even declining invitations to the White House.

In 2005, Domino lost his Lower 9th Ward home and possessions to Hurricane Katrina—and was briefly rumored to have perished in the storm. Trapped by the rising waters, he was rescued from a second-story window. Domino returned and rebuilt. He would give his final public performance in 2007 at Tipitinas, benefitting the Foundation’s efforts to support local musicians.

While his influence was worldwide, inspiring Jamaican ska, the British Invasion, and American rock, Domino was always a New Orleanian at heart. While he would live out his final years across the canal in Harvey, his roots never left the city he loved.

--

Anyone over the age of 40 or someone who is a born and raised New Orleanian is likely to know about Fats Domino. This is a name that you couldn’t avoid hearing in the 1950s and early ‘60s. The sounds of this great musician’s hits filled the airwaves during this time and cemented him as one of the best musicians of all time. To help better explain this music legend’s legacy, here is a timeline exploring the life of Fats Domino.

1920s

On February 26, 1928, the future legend Fats Domino was born as Antoine Domino Jr. Being born in New Orleans allowed him to be exposed to a lot of the local culture fairly early on in his life, which would later be one of the main inspirations for him pursuing his career in music.

1930s

As a young child, Antoine’s family was given an old piano that he would instantly fall in love with. With the musical assistance of his brother-in-law, Antoine began to take formal piano lessons and actually decided to drop out of primary school in order to further concentrate on his piano playing.

1940s

Antoine marries his long-time partner, Rosemary Hall, and begins playing some paid gigs at his sister’s Philomena’s fish fry, which eventually leads to him meeting several local musicians. He would soon get hired as a performer at the Robin Hood club as well as the Hideaway Club and Club Desire. During this stint as a club performer, he was given the nickname “Fats” because of his size.

One of the many musicians he played with as a club performer was Dave Bartholomew, who he would develop lifelong writing and producing partnership with. Fats was signed to Imperial Record Company in 1949 and released what is considered one of the first rock ‘n’ records as part of Dave’s band, which was called The Fat Man.

1950s

Fats begins to tour as part of Dave’s band but experiences very little success. He would then begin to write a string of hits as part of his own band, which included the song “Goin’ Home” that ended up being his first number one hit on the R&B charts. By the middle of the decade, Fats had established himself as a major player in the R&B industry with his long list of hits that included “Poor Me,” “Ain’t That a Shame,” “I’m in Love Again,” “My Blue Heaven,” and “All By Myself.”

In 1956, Fats released his cover of “Blueberry Hill,” which would launch him to international fame and land him on The Ed Sullivan Show.

1960s and ‘70s

Now is considered one of the biggest rock ‘n’ roll musicians in the world, Fats began to do tours in Jamaica and Europe. He also writes some more minor hits but nothing that is as popular as his older songs.

1980s and ‘90s

Fats begins winning several prestigious awards such as the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and being inducted into the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame. He was also awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton in 1998.

2000s and ‘10s

Fats manages to make it through Hurricane Katrina but he is one of the millions of people that lost their homes during the natural disaster. In 2006, Fats released his final album titled Alive and Kickin’ and enjoyed his relatively quiet life in New Orleans. At the age of 89, Fats, unfortunately, passed away on October 24, 2017.

1 comment

Ky E.S. Mason

Wonderful tribute to a man who will never be forgotten! Condolences to all New Orleans. Keepin’ the music playin’ is the best we can give “Fats” in heaven, for all the joy he gave us!

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.