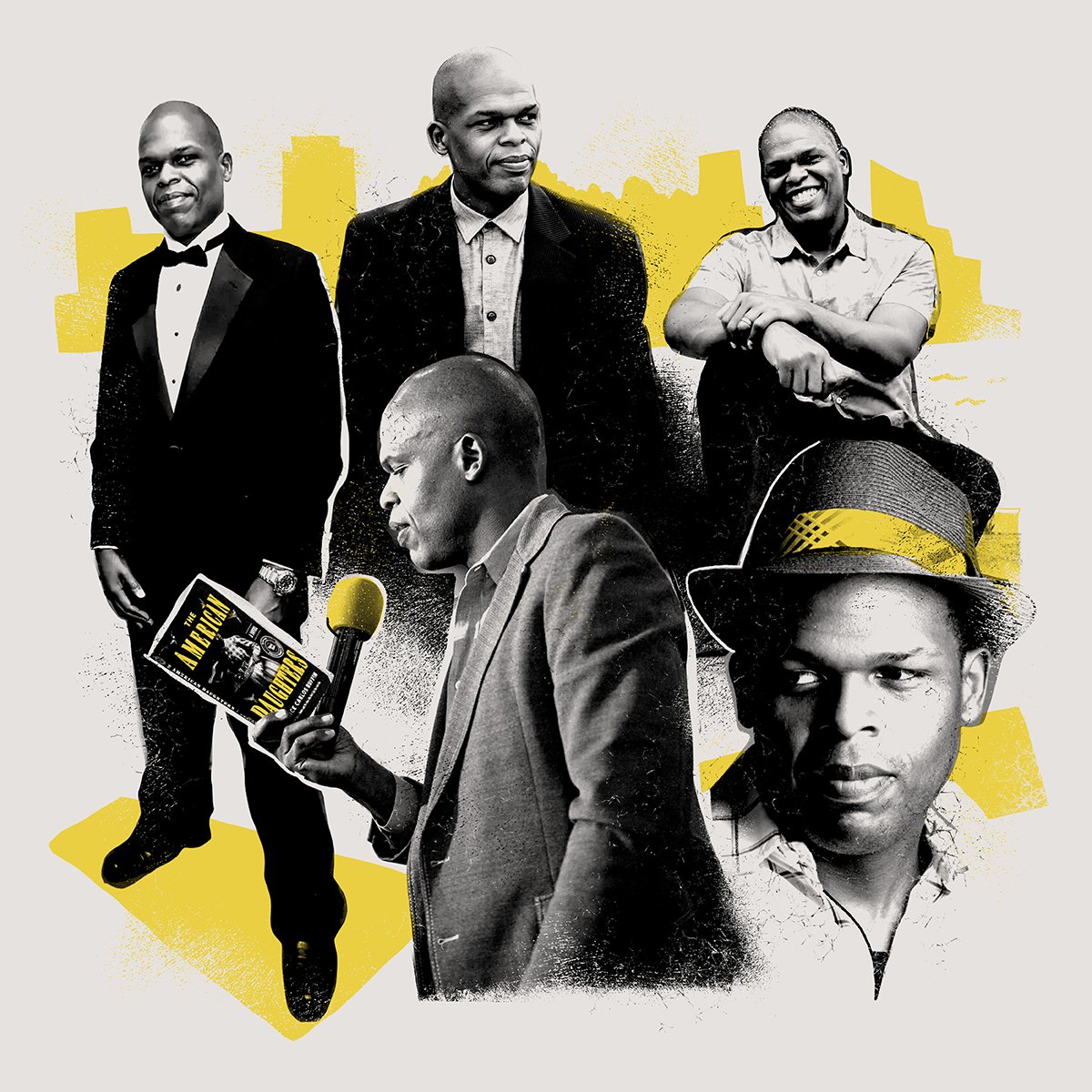

Bill Banzai White

Tennessee, 2025

It started well before the tshirts. There was an energy among those who started Dirty Coast to move the city of New Orleans towards being more equitable and progressive, more accountable to local residents and their needs, more forward thinking. There were small discussions, salons, speakers, events, fostering a positive sense of creating a vision of New Orleans moving forward economically, politically, and socially, all the while preserving and enhancing the rich cultural history of New Orleans. We all had that feeling that we could make what we all knew was the only place for us to ever be an even better place to live and work for residents and future generations alike. We were critical, but we loved our city’s culture and rich history. We respected it, and it was the foundation of our drive to make New Orleans a better place.

There were setbacks, to be sure. The overturning of New Orleans minimum wage efforts by the state court in 2002. The building of the Walmart in the former St. Thomas projects neighborhood.

By 2005, Dirty Coast as a concept was playing with these hopes. The first tshirt I can remember was called “I AM New Orleans!” and for me that meant that I represented a “new” New Orleans, more attitude than action perhaps, but actions don’t begin without the philosophy to provide the focus and vision. “I AM New Orleans!” I live it every day, I appreciate and celebrate the culture, I support local businesses over megastores, I listen to local radio, I support our musicians, and I support our local events. I “vacation” in my own city—why would you vacation anywhere else? New Orleans—proud to call it home.

There was a sense in 2005 that we had the potential to turn the corner in New Orleans. Preserving the culture and the ambiance of the city, while creating an attitude towards new economic development opportunities that could begin to level the playing field. To reduce crime, we needed good jobs for our residents. We needed to move beyond the harbor and tourism industries and try to diversify our economy. We had seven higher education institutions in the city—a center for brainpower and forward thinking. We had the tools to make our city economically sound.

Anyone paying attention, though, knew the biggest impediment to attracting economic development into the city was our levees. Specifically, we knew that any hurricane above a “Cat-3” directly hitting the city had the potential to put the whole city under water. Hell, there was even an exhibit at the Children’s Museum that illustrated how quickly the city would fill if the levees were breached. Building the levees to Cat-5 standards would give investors confidence to locate or build their interests in the city.

And then Katrina hit.

For many of us, it would take a month or more to come back to the city. Most of us weren’t living in the housing we had left behind because of the damage or the mold or both. We were staying with friends fortunate enough to still have livable housing, and for me that was in the French Quarter. After spending quite a bit of time gutting my home, I realized that the immediate needs of my family was paramount to trying to come back to New Orleans. I was offered a position in Texas and took it. I had a feeling that I would not be coming back home unless it was to visit. Twenty years later and we still remain exiled in the diaspora.

Things would remind us of home. We would hear the interviews on NPR while we were going to work. One I remember was a rebroadcast interview with Dr. John completed before the storm. Another was an interview with Allan Touissant and Elvis Costello. It would be the first time I heard Allan’s “Tipitina And Me”—a somber ode to the destruction of Katrina. Touissant takes “Tipatina” and plays solo piano slowly and in minor chords. I was balling my eyes out as it played.

And Dirty Coast was there for us. For all of us in exile.

“Be A New Orleanian Wherever You Are.” Yeah you right! Once you had that “Bless Their Heart” Gumbo cooked for us by well-meaning people, you knew you had to take charge of helping outsiders experience the culture and personality of New Orleans. “Be A New Orleanian Wherever You Are!” I live by that motto every single day.

Ashley Morris, a local blogger who captured life in New Orleans before and after the storm, finally had enough with the outside critiques of the city and posted his classic blog “Fuck You You Fucking Fucks!” His blog post (published on November 27, 2005) defended New Orleans’ identity while also exposing hypocrisy in disaster recovery, condemning exploitation by outsiders, and expressing rage at institutional betrayal. Disaster, recovery, and double standards. Rage as a form of grief. He spoke for all of us in the diaspora. He spoke for all who remained and were rebuilding our city. Dirty Coast captured those feelings and emotions with the “FYYFF” tshirt. Ashley’s tattoo emblazes the center of the tshirt. Sinn Féin—“We Ourselves.”

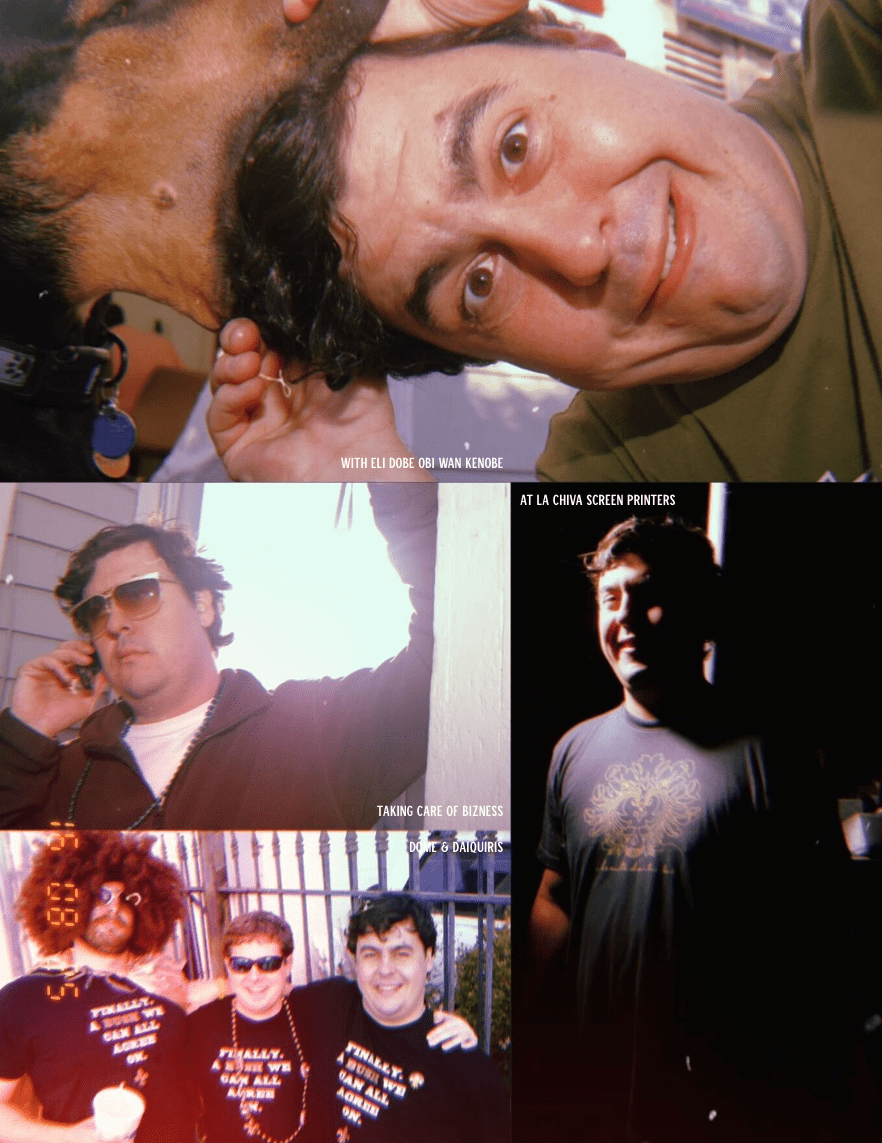

The Saints—oh the Saints. “Finally A Bush We Can All Agree On!” The “inside” jokes that gave a nod to being a New Orleanian. “Mother Would Approve!” “Save The Sazerac.” “Crawfish Pi.” “WWOZ.” Local culture fostering local pride beyond New Orleans. It seemed like every month something creative and personal was being produced by Dirty Coast that hit home for those of us not home yet.

As time went on and the years passed, the tshirts became a sort of “identification card” amongst ourselves in places like Atlanta or Houston or Austin or San Francisco or many other places around the world. You’d see someone with a Dirty Coast tshirt and you knew that we both were somehow connected to each other. A nod, a wave, a “whereyat?” yell. We’d stop, we’d talk, we’d reminisce, we’d go out for a drink. We’d slow time down to just hang out a bit and reaffirm that we truly knew what it meant to miss New Orleans.

How the hell can a tshirt capture all those emotions? A sense of pride, a sense of place, a sense of identity? And yet, Dirty Coast did it. The political commentary and inside jokes help all of us focus on the continuing efforts to help build a better city. The tshirts act as an educational tool for those who have migrated to our city and need to be reminded about how important our culture is. “Let’s Have Lunch and Talk About Dinner.” “The Knife Stays In The Box.” “Listen To Your City.” They bring a smile to our faces, they tell a story of where New Orleans is and where it hopes to go. They unite us in exile, they endear us to the only place we could ever live and want to fight for. The tshirts represent us—being New Orleanians wherever we are.

It's All Good!

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.